The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was launched to orbit just two years ago, but already it’s starting to redefine our view of the early Universe.

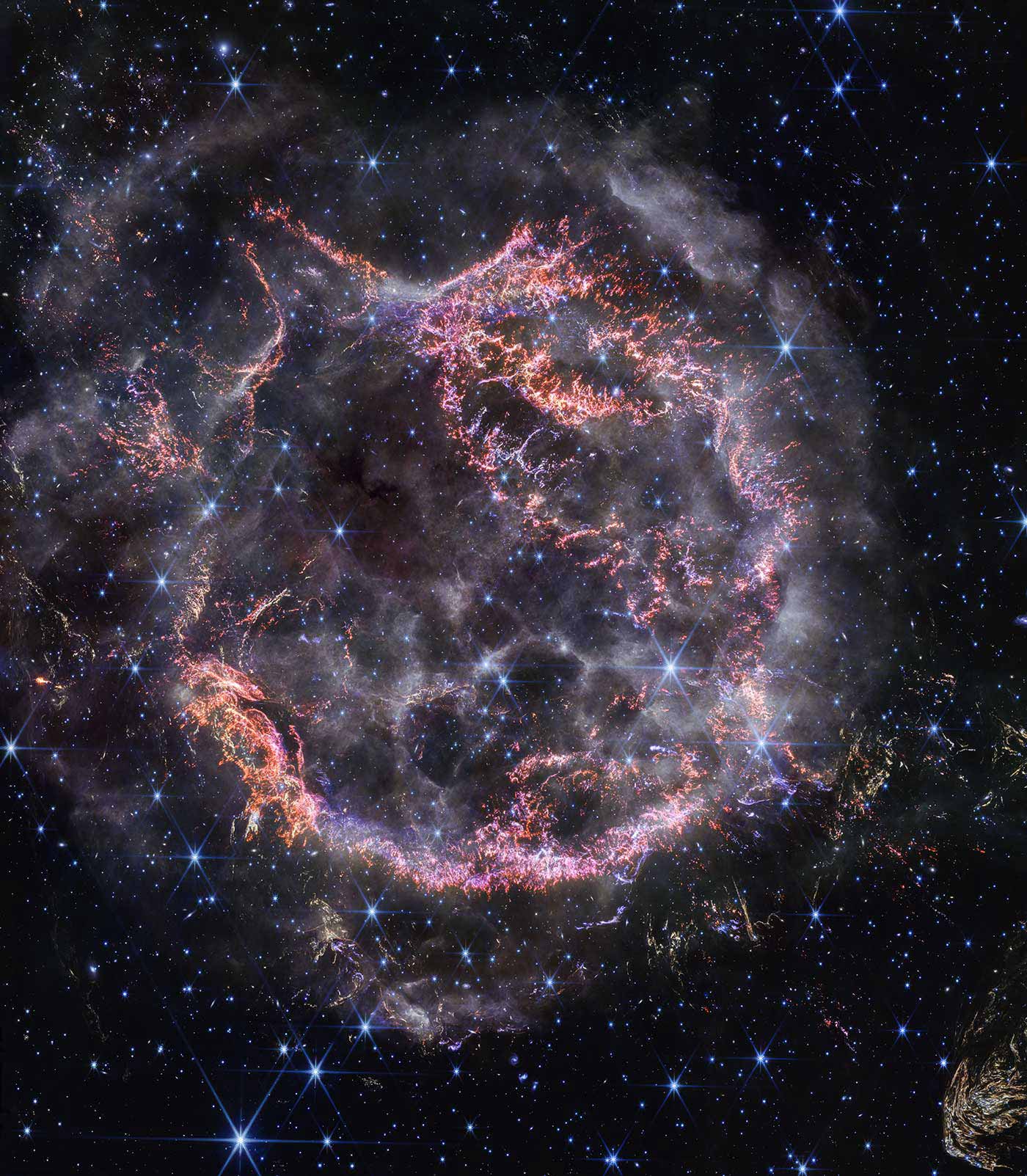

CASSIOPEIA A The expanding shells of debris from Cas A, an exploded star, or supernova. The main ring is about 15 light-years across.

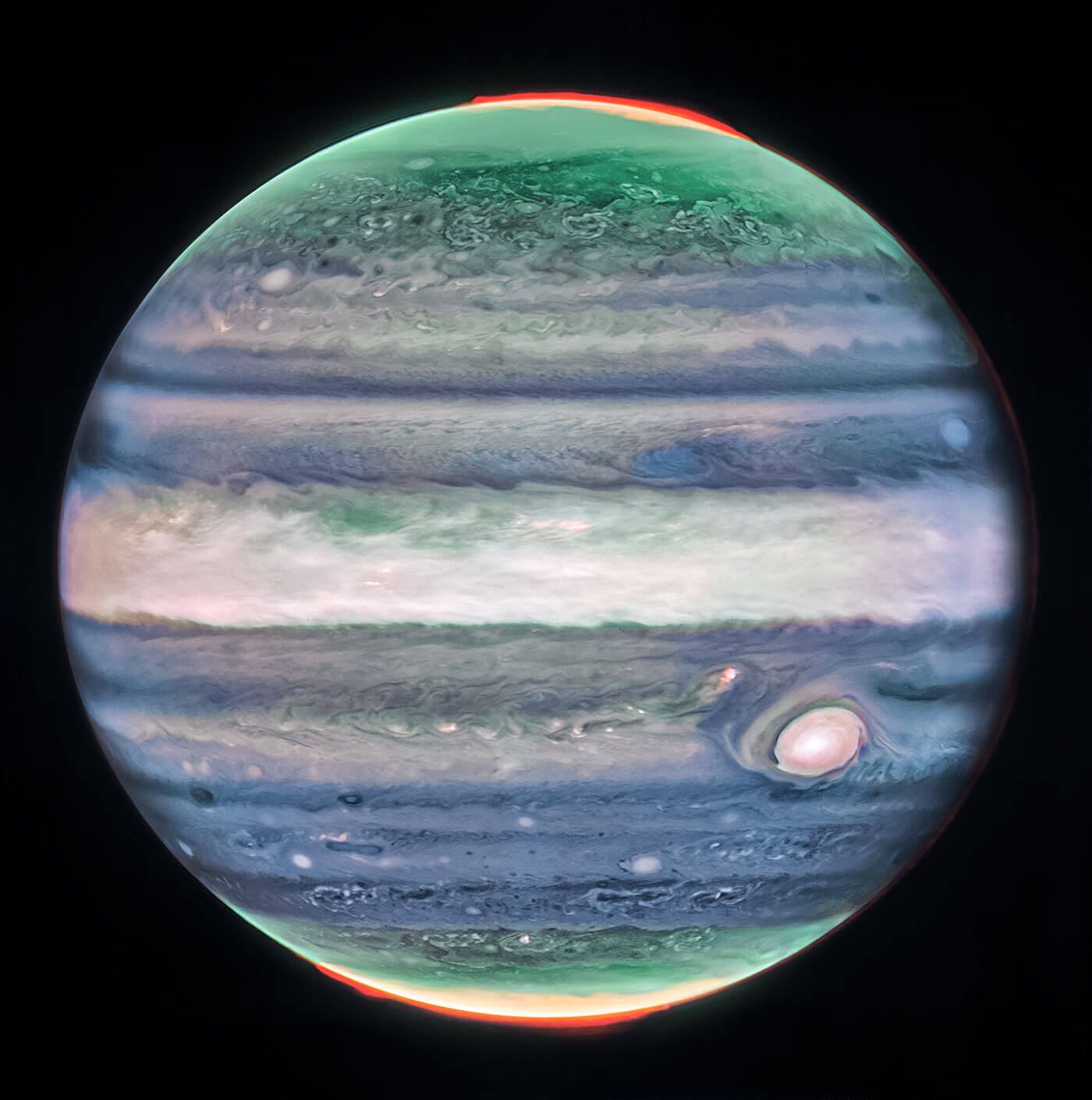

JUPITER The largest planet in the Solar System, Jupiter, viewed in infrared light. The brightest features are at the highest altitudes – the tops of convective storm clouds.

Without really stretching its capabilities, the infrared observatory has been peering deep into the cosmos to show us galaxies of stars as they were up to 13.5 billion years ago.

A lot of them are brighter, more massive, and more mature than many scientists thought possible so soon after the Big Bang, which occurred 13.8 billion years ago.

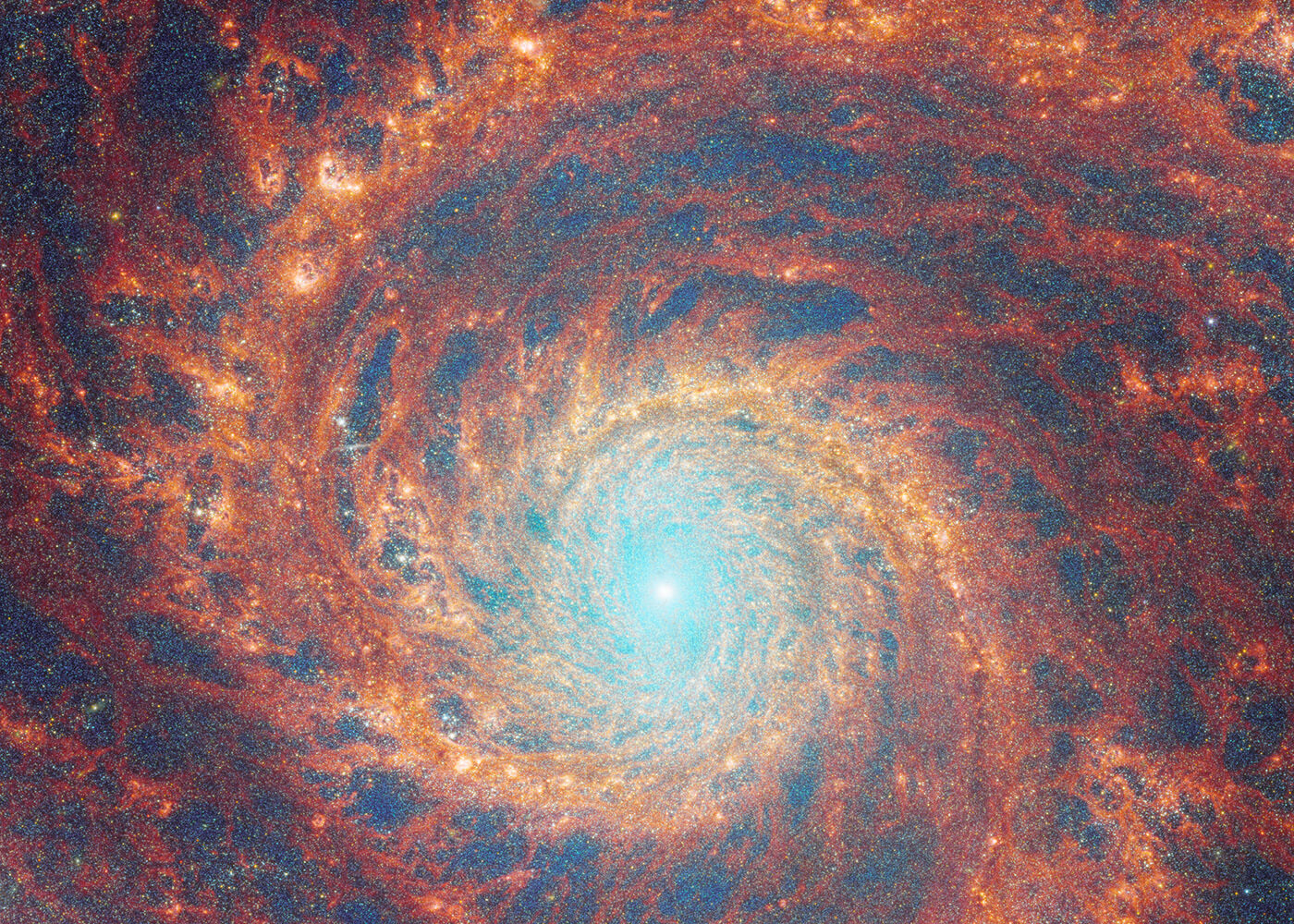

“We certainly thought we’d be seeing fuzzy blobs of stars. But we’re also seeing fully formed galaxies with perfect spiral arms,” said Prof Gillian Wright.

“Theorists are already working on how you get those mature structures so early in the Universe. In that sense, Webb is really changing scientific thinking,” the director of the UK Astronomy Technology Centre told BBC News.

M51 The Whirlpool Galaxy can be seen in the night sky with just binoculars. Here, the most powerful space telescope ever launched uses its incredible capabilities to study the intricate spiral arms.

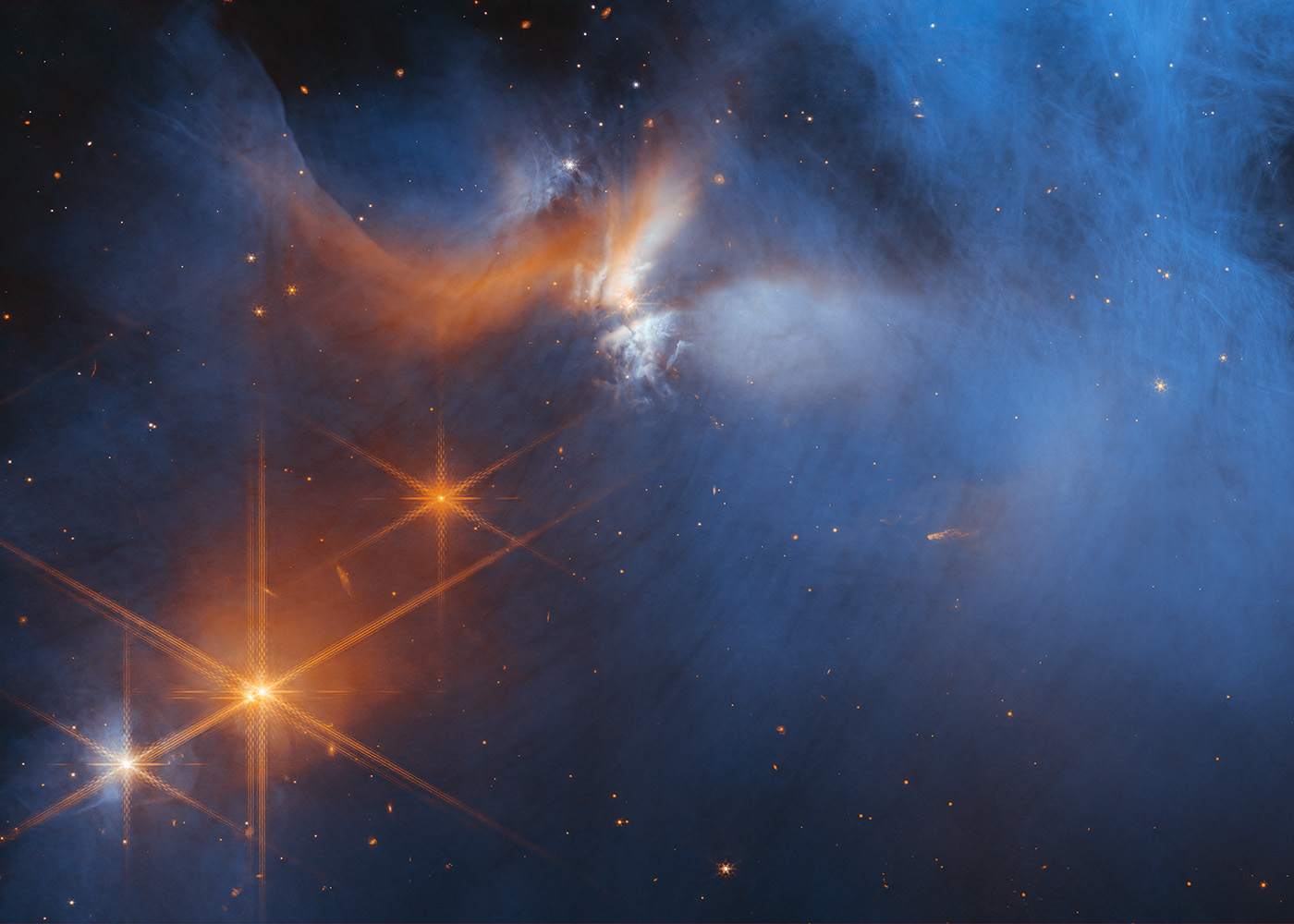

CHAMELEON I The Chameleon I molecular cloud is about 630 light-years from Earth. It’s here, at temperatures down to about -260C, that Webb has detected types of ice grains not previously observed.

SAGITTARIUS C Webb looks to the centre of our galaxy, close to where a supermassive black hole exists. This region of space contains tens of thousands of stars, including many that are birthing inside the bright pink feature at centre-left. The cyan colour highlights excited hydrogen gas.

And it’s not just the efficiency with which these early galaxies were able to form their stars that’s been a surprise, the size of their central black holes has been a marvel, too.

There’s a monster at the core of our Milky Way that’s four billion times the mass of our Sun. One theory suggests such behemoths are made over time by accreting lots of smaller holes produced as remnants from exploded stars, or supernovae.

“But the preliminary evidence from JWST is that some of these early giants may have completely bypassed the star stage,” said Dr Adam Carnall from the University of Edinburgh.

“There is a scenario where huge clouds of gas in the early Universe could have collapsed violently and just kept going, straight to being black holes.”

NGC 3256 This is what you get when two galaxies crash into each other, an event estimated to have occurred about 500 million years ago. The collision drives the formation of new stars that then illuminate the gas and dust around them.

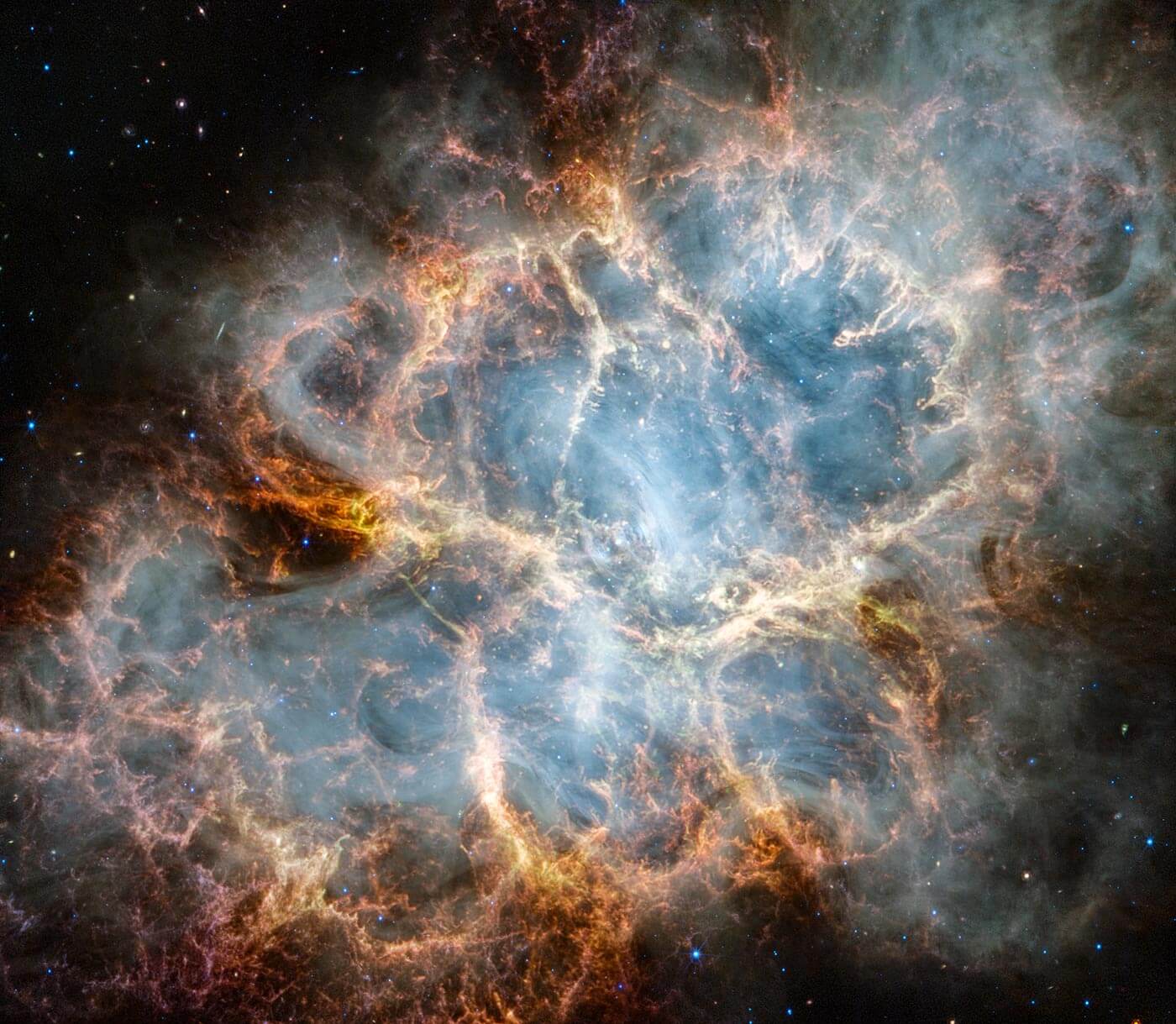

CRAB NEBULA The famous supernova remnant first recorded by Chinese astronomers in 1054. It’s located some 6,500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Taurus.

When James Webb was launched at Christmas 2021, it was thought it might have 10 years of operations ahead of it. The telescope needs its own fuel to maintain station 1.5 million km from Earth. But the flight to orbit on an Ariane rocket was so accurate, it’s estimated now to have fuel reserves for 20 years of life, if not longer.

This means, rather than racing through their observations, astronomers can afford take a more strategic approach to the telescope’s work.

“We thought we’d be skimming cream; we no longer need to do that,” said Dr Eric Smith, Webb’s programme scientist at the US space agency Nasa.

One activity that’s sure to accelerate is the practice of making “deep fields”. These are long stares at particular patches of sky that will allow the telescope to trace the light from the faintest and most distant galaxies. It’s how Webb is likely to spot the very first galaxies and possibly even some of the very first stars to shine in the Universe.

SATURN The famed ringed planet appears quite dark to Webb in this image because methane in the planet absorbs infrared light strongly. Three of Saturn’s moon are seen to the left.

HH212 A baby star, no more than 50,000 years old, launches energetic jets from both poles that light up the molecular hydrogen in pink. The entire structure is 1.6 light-years across.

The Hubble telescope famously expended many days just looking at a single corner of the cosmos. “I don’t think we’ll need the hundreds of hours of exposure that Hubble used, but I do think we’ll need multiple deep fields,” said Dr Emma Curtis-Lake from the University of Hertfordshire.

“We’ve already had some quite long exposures with JWST and we’re seeing quite a lot of variation. So, we can’t put everything into one teeny-tiny area because there’s no guarantee we’ll find something super-exciting.”

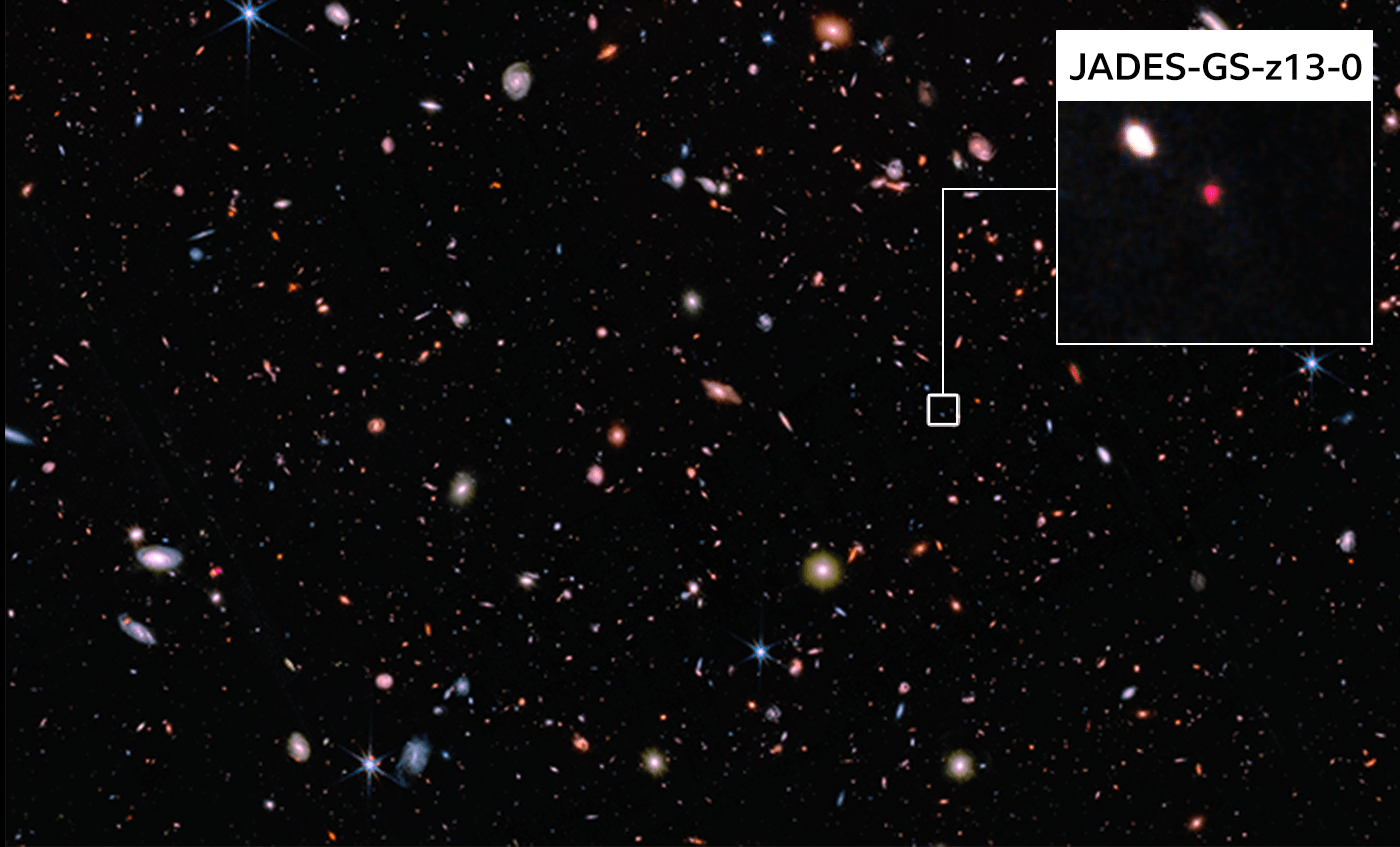

JADES The JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, otherwise known as Jades, has the earliest confirmed galaxy, called JADES-GS-z13-0, which is observed at just 325 million years after the Big Bang.

STAR CLUSTER IC 348 Wispy filaments of gas and dust stream between a cluster of bright stars. Webb found the lowest mass brown dwarf, or “failed star”, in this image – an object about three to four times the mass of our Jupiter.

The Space Telescope Science Institute’s Dr Massimo Stiavelli dreams of spotting a star that is primordial – that has the signature of the original chemistry that emerged from the Big Bang; that hasn’t been polluted with elements that were forged only later in cosmic history.

“We’ll need to see them as supernovae, when they explode,” the head of the Webb mission office said.

“To achieve this, we need to start looking at the same patches year after year to catch them before and just after they go off. They’ll be extremely rare and we’ll need to be very lucky.”

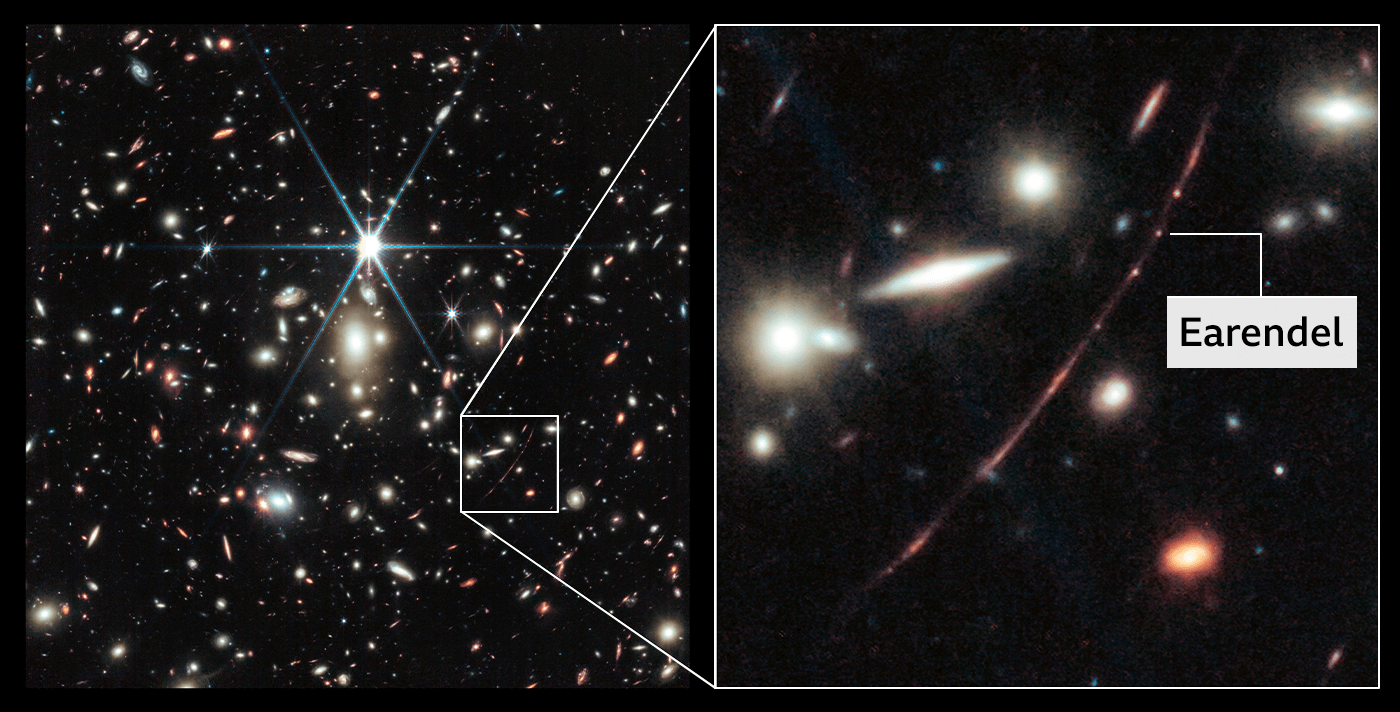

EARENDEL The most distant single star observed to date is called Earendel. James Webb confirmed its light has taken 12.9 billion years to reach us. Its light has been boosted by the gravity of foreground galaxies.

ORION NEBULA The famous star forming region can just about be seen by the naked eye as a smudge on the sky. It would take a spaceship travelling at light-speed a little over four years to traverse this Webb scene.

Marvel at the extraordinary collection of James Webb pictures on this page – from the most distant reaches of the Universe to the nearby familiar objects in our own Solar System.

It’s amazing to think that imaging isn’t actually the telescope’s majority workload.

More than 70% of its time is spent doing spectroscopy. That’s sampling the light from objects and slicing it up into its “rainbow” colours. It’s how you retrieve key information about the chemistry, temperature, density and velocity of the targets under study.

“You could think of Webb as a giant spectrograph that takes the occasional nice picture,” joked Dr Smith.

RHO OPHIUCHI This cloud complex is the nearest star forming region to Earth, being just 400 light-years away. The star lighting up the white cavity is just a few million years old.